In addition, you can read my thoughts on the lack of traditional "labels" at the relic-stuffed Christian Sanderson Museum here. Or, you can read about the early nineteenth-century snuffbox complete with family provenance here. In the case of the teabowl and saucer and the snuffbox, I verified (and invalidated) some of the information that came with the objects. In the case of the snuffbox, a genealogist emailed me a photograph of a descendant of the snuffbox's original owner. Blogging about my collection provides me with a creative outlet and others with fodder for their own research. Relics by definition come with enthusiasm for the past, and sharing that enthusiasm with someone, even if just through a note, makes history more relevant and meaningful to each of us.

But relics, including those I have written about thus far, are also highly problematic. People have emotional--sometimes firsthand--attachments to the events, people, or ideas some objects commemorate. Relics are powerful. Yet sometimes you're too far removed from events or people to "get" all messages the relic embodies.

|

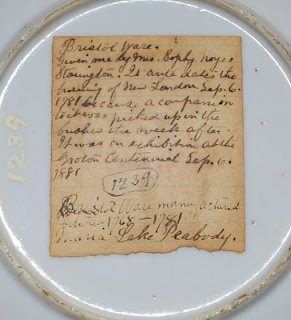

| John Brown relic, c. 1900, wood, paper, and metal, 6.5" H x 7" W (Nicole Belolan's Collection) |

An excellent American literature class I took in college fueled my most sustained contemplation of John Brown. In that class, we read Herman Melville's "The Portent," which quickly became one of my favorite poems (which says a lot since I'm not a huge fan of poetry, yet I am a big fan of Melville):

The Portent (1859)

Hanging from the Beam

Slowly swaying (such the law),

Gaunt the shadow on your green,

Shenandoah!

The cut is on the crown

(Lo, John Brown),

And the stabs shall heal no more.

Hidden in the cap

Is the anguish none can draw;

So your future veils its face,

Shenandoah!

But the streaming beard is shown

(Weird John Brown),

The meteor of the war.

Thus the John Brown I knew was a well-intended if not radical American who fought (or terrorized) others on behalf of millions of enslaved Americans. And so that explains what I didn't realize which "John Brown" I should associate with the 1824 tannery pictured on the relic...who knew Mr. Brown had--or at least tried to succeed at---a proper occupation as a tanner! (In the very least, this makes Brown more human.) Even through Melville referenced Brown's beard, the Brown I "remember" is this man:

|

| Earliest known likeness of John Brown, c. 1846-1847, daguerreotype by Augustus Washington (National Portrait Gallery) |

Few Americans cut a more arresting likeness than Mr. Brown. Brown's visage was striking, and his pose--his right hand raised as if making a promise, his left hand holding what many have speculated was the flag or standard that represented his alternative form of the underground railroad--was also. Most of us can only hope to conjure in our own portraits the self-confidence Brown exuded here.

Yet the Brown our Melville wrote about in "The Portent"--streaming beard and all--evoked a different Brown, the Brown printed on the relic's underside:

I will come clean with you here and admit that I was not familiar with this likeness of Brown (or, at least, I had not made the connection between Melville's Brown and the Brown likenesses that included beards). Yet this is the Brown most artists have used in their representations of Brown, and by all accounts, this is a line drawing adaptation of a Brown photographic likeness with which I should be most familiar. Not only that, but I was unfamiliar with Brown's (apparently) well-documented stint as a tanner. For me, the relic was troublesome because I wasn't familiar enough with the Brown Americans knew around the turn of the twentieth century.

Yet plenty of Brown experts know the beard's history. According to scholars at the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History at the New-York Historical Society, Brown grew this beard as a disguise, and he wore the beard for just the last few months of his life. As you peruse the "further reading" links below, you'll find the many post-Brown and post-Civil War likenesses of Brown that featured the beard.

And so once I verified that the back of the relic included a well-known (though not to me) likeness of Brown, I began to understand more about the source of the relic's "power" as an object. But what of the tannery? Here's a detail of the label above the portrait:

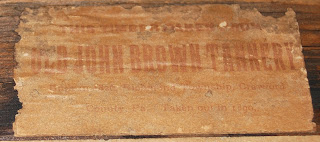

The text, now faded, reads:

THIS TIMBER TAKEN FROM/OLD JOHN BROWN TANNERY/Built in 1826, Richmond Township, Crawford/County, Pa., Taken out in 1890

Is this really a shingle from the Brown tannery in Pennsylvania? It's hard to say. Based on the image of the tannery on the postcard, it certainly seems plausible. Poking around the internet, I found no other tannery relics. I did find others such as the pikes (hand-held weapons, like bayonets) Brown commissioned from a blacksmith and intended to use in his assault on slavery. And it seems you can visit a bona fide John Brown Tannery site, as documented by one blogger here and here.

Brown, it seems, is far less likely to resonate with contemporary Americans the way he might have even as recently as he did during the mid twentieth-century Civil Rights movement. Through a casual survey I conducted among friends and relatives, many of whom are history enthusiasts, none had a deep understanding of Brown, his role in inciting the Civil War, or his impact on Civil Rights leaders. Thus among Americans (myself included), Brown no longer holds our imaginations the way he once did. Even I recalled the more obscure likeness, not the more "popular" one. What I like about the tannery relic is that it puts Brown into his proper historical and human context as a somewhat ordinary man who had (what we now consider) noble goals that he accomplished through extraordinary means. It also captures an era (now lost) in which Brown held extraordinary power in generating enthusiasm for the Civil War and African American Civil Rights. This relic, souvenir, or whatever you want to call it (scholars debate what term is most appropriate) commemorates a man, or a worker and his tannery--someone with whom non-radicals could relate--not simply a militant abolitionist or a terrorist. This relic embodies a human, everyday story representative of historians' recent efforts to integrate Brown's militancy into the larger arc of Civil Rights advocacy spanning the eighteenth through the twentieth centuries. Ultimately, Brown's actions, while extreme, put him on the right side of history. This relic tells part of that tale.

And so despite the fact that I'm a historian, I didn't "get" all the signs on this relic at first. There has been some debate in recent weeks about welcoming the general public into galleries sans interpretive labels. But as my relationship with my bearded John Brown relic suggests, sometimes, even the "experts" need a hint.

Further ReadingBrown, it seems, is far less likely to resonate with contemporary Americans the way he might have even as recently as he did during the mid twentieth-century Civil Rights movement. Through a casual survey I conducted among friends and relatives, many of whom are history enthusiasts, none had a deep understanding of Brown, his role in inciting the Civil War, or his impact on Civil Rights leaders. Thus among Americans (myself included), Brown no longer holds our imaginations the way he once did. Even I recalled the more obscure likeness, not the more "popular" one. What I like about the tannery relic is that it puts Brown into his proper historical and human context as a somewhat ordinary man who had (what we now consider) noble goals that he accomplished through extraordinary means. It also captures an era (now lost) in which Brown held extraordinary power in generating enthusiasm for the Civil War and African American Civil Rights. This relic, souvenir, or whatever you want to call it (scholars debate what term is most appropriate) commemorates a man, or a worker and his tannery--someone with whom non-radicals could relate--not simply a militant abolitionist or a terrorist. This relic embodies a human, everyday story representative of historians' recent efforts to integrate Brown's militancy into the larger arc of Civil Rights advocacy spanning the eighteenth through the twentieth centuries. Ultimately, Brown's actions, while extreme, put him on the right side of history. This relic tells part of that tale.

And so despite the fact that I'm a historian, I didn't "get" all the signs on this relic at first. There has been some debate in recent weeks about welcoming the general public into galleries sans interpretive labels. But as my relationship with my bearded John Brown relic suggests, sometimes, even the "experts" need a hint.

More more on John Brown, check out David S. Reynolds's recent John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights (2005). You can also take a look at the Virginia Historical Society's online exhibition about John Brown in American (but not mine!) memory and Gilder Lerhman's online exhibition about Brown and his career and legacy as an abolitionist. I also suggest Adam Gopnik's review of David S. Reynolds's John Brown, Abolitionist (2005). In the course of reviewing the book, Gopnik provides a great overview of how historians' interpretations of Brown have changed over time. You may also find this Library of Congress "lesson" on the song "John Brown's Body" useful.

For a classic essay on relics, see Rachel T. Mains and James T. Glynn, "Numinous Objects," The Public Historian 15, 1 (Winter, 1993): 8-25. Relic "scholarship" is booming these days. Let me start you off with something light but "smart" (not to mention well-illustrated): William L. Bird, Jr., Souvenir Nation: Relics, Keepsakes, and Curios from the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History (2013).

I'd love to hear about your favorite books on memory and relics, not to mention the nature of your familiarity with John Brown's beard. I'd also be interested to hear from teachers (secondary or college) as to the extent to which you "teach" John Brown and his raid. submit a comment below, or email nbelolan at udel dot edu.

No comments:

Post a Comment