As Tyler and I were leaving our favorite antique mall in Lewes, DE, last summer, I plucked a photograph jauntily resting on a table with other photos. I noticed two children and what I presumed to be some sort of pet pony.

Intriguing, but not really what I collect. (Perhaps of interest to the eminent Pet Historian?) I returned the photo to its perch as quickly as I picked it up.

"Wait," Tyler said.

I looked at it again. This time, I saw what Tyler saw: a painted screen.

"Whoa, cool!," I said. "Perhaps it's from Baltimore."

I collected my loot (hard to resist at just $8) and walked briskly to the cash register, eager to do some reading on the topic. I had recently seen a segment on the CBS show Sunday Morning about Baltimore painted screens, so it was cool to see a photograph of one so soon thereafter. Then, just a few months after this acquisition, I saw the book about Baltimore's painted screens on sale for just $10 at the National Museum of American History. Another steal!

It was time to do more reading.

Baltimoreans have been painting screens since about 1913. The provided passers-by with something nice to look at from the outside. They also allowed air to flow freely in the warm summer months while obscuring view to the inside of the house from the sidewalk. People have been painting screens since at least the eighteenth century. But in downtown Baltimore, it all started with a grocer. You can read more about this fascinating history and the state-of-the-craft in Elaine Eff's book The Painted Screens of Baltimore.

It's hard to say with certainty if this photo was taken in Baltimore. It looks to me like the kids are from around the 1910s or so. They certainly could be Baltimore kids.

Recognize them?

Either way, I love the backdrop they chose for the photograph. And there's probably a story behind their four-legged friend as well.

What would you paint on your screen?

Further Reading

Elaine Eff, The Painted Screens of Baltimore: An Urban Folk Art Revealed (University Press of Mississippi: 2013)

Painted Screen Society of Baltimore

I bought it. But, what is it, how did it become what it is, and what does it mean? And other thoughts on material culture. by Nicole Belolan

Showing posts with label material culture. Show all posts

Showing posts with label material culture. Show all posts

Thursday, December 31, 2015

Sunday, October 11, 2015

Material Culture Minute: Map Memories

Browsing the aisles of a favorite antique mall in Lewes, DE, a few weeks ago, I came across a 1958 "how-to-get-there" street guide for New York City.

I was going to leave it. It fits in the palm of your hand, but it's kind of thick and bulky. Tyler and I have a large binder of ephemera we've accumulated over the past few years for teaching purposes. Do we really need an outdated map?

Of course we do! We're historians. New York is my favorite city. And I can't tell you how often I've gotten important social-historical details from historic city directories. Students, I think, could get a lot out of this. Who was the audience, and how can you tell? Why was Roosevelt Island known as Welfare Island? What can you deduce about the 1958 world political scene based on the list of consulates?

Not only that, but it occurred to me that I was looking at my dad's New York. Born there in 1939, he was 19 when this "how to get there" map was published by the Barkan System. I thought it might be fun to take a look at it with him and see what he recognized and talk about what's changed.

Sure enough, my dad was full of stories, memories drawn out by looking through the directory of places of worship, schools, and hotels and spending some time with the large street and transportation map.

Perhaps my favorite memory revolved around television. We were browsing the list of local TV stations (just seven) when Tyler asked my dad about when his family got a TV.

My dad came back with a story about the time he was at his parents' house (by this time, my dad's family had moved from the Lower East Side in Manhattan to Queens) and some of his friends--one in the FBI and another in the Secret Service--stopped by to watch a game on the family's new color TV.

While munching on snacks and enjoying some drinks, my dad's mom walked into the room, opened the top drawer of a bureau to fetch some tablecloths, and started--"oh, my!"--at the government-issued firearms my dad's buddies stored there for safekeeping while cheering on their favorite team.

I'm not sure who won or what sport they were watching. But who cares? For $4, I got some great anecdotes and another treasure to add to our bursting binder of ephemera fun.

Tuesday, May 5, 2015

Desiccated Toys and Play

I cannot resist desiccated ephemera.

And so that's why I came home from the Allentown Paper Show on April 25 with spices and other relics from the Bible Lands.

That's right, I snatched up my very own Sunday-School Teachers' Museum Collected from the Bible Lands. Dreamed up and manufactured by Paul S. Iskiyan's School for Christian Workers in Springfield, MA, around 1890, this gem contains twenty-two specimens of natural substances featured in the Bible. Based on other extant examples I found online (glad to see I'm not the only one saving saffron that's turning to dust), mine is incomplete, is missing an explanatory booklet, and is in poor condition. As you can see, each specimen is in varying degrees of preservation. The sackcloth (is this sackcloth?) has seen better days (as Tyler put it).

As a self-proclaimed heathen, I had never heard of some specimens. Was I really looking at Daniel's encapsulated pulse, as the cover of this better preserved example the National Museum of Play told me?

Yes and no. Pulse is a seed and not just a biological phenomenon. Similarly, circa 1890 children probably were equally unfamiliar with some of the items. Whereas we cook regularly with lentils in our house, they weren't all that common in American kitchens until World War II.

But that's the point of the "Museum." It's an example of an "object lesson." As the leading scholar on the subject Sarah Carter put it, object lessons gave children a way to learn about "the world through their senses, instead of through texts and memorization." Sarah explains that this "lead[] to new modes of classifying and comprehending material evidence drawn from the close study of objects, pictures, and even people."

In this case, Iskiyan and the teachers who used this treasure for teaching deployed it to make the Bible and its message--both of which are some of the least material concepts with which Americans grappled (and continue to do so)--more real to children. Presumably, they hoped spirituality would follow.

Turns our this particular "museum" held shelf space at another popular museum before it found its way to the Allentown Paper Show and into my clutches. I learned from the dealer that when Merritt's Museum of Childhood in Douglassville, PA, (known first as Merritt's Early Americana Museum and then merit's Historical Museum, according to this article) closed its door a few years ago, an auctioneer sold the Sunday School Teacher's Museum along with thousands of other museum artifacts. Sold by Pook and Pook and Noel Barrett, the Museum content ranged from a late nineteenth-century English scale model of a butcher shop ($73,700!) to groups of miniature pewter hollowware.

I got curious about the Butcher shop (what can I say, I like meat), particularly since I guessed (correctly) the "North Carolina Institution" that acquired it was likely the toy museum at Old Salem Museums and Gardens in North Carolina. In the course of googling the Butcher shop (photo below from here)...

...I also learned that Old Salem, which is perhaps best known for its significant collection of Moravian and Southern decorative arts, closed the toy museum in 2010 and sold the collection.

I saw the Old Salem toy collection intact when I first visited in 2008 and had no idea it had been dissolved -- but it makes sense given Old Salem's mission. All proceeds went toward conservation and other collections-related activities associated with the core Moravian and Southern collection.

It's striking that Barrett alone has liquidated four toy museum collections. What does that say about our changing interest in learning from traditional toys and play in museum settings?

I'm not sure where the butcher shop is now, but I hope that like my own piece of Merritt's Museum of Childhood History, it's somewhere teaching someone an object lesson.

|

| Nicole Belolan's Collection |

And so that's why I came home from the Allentown Paper Show on April 25 with spices and other relics from the Bible Lands.

|

| Nicole Belolan's Collection |

That's right, I snatched up my very own Sunday-School Teachers' Museum Collected from the Bible Lands. Dreamed up and manufactured by Paul S. Iskiyan's School for Christian Workers in Springfield, MA, around 1890, this gem contains twenty-two specimens of natural substances featured in the Bible. Based on other extant examples I found online (glad to see I'm not the only one saving saffron that's turning to dust), mine is incomplete, is missing an explanatory booklet, and is in poor condition. As you can see, each specimen is in varying degrees of preservation. The sackcloth (is this sackcloth?) has seen better days (as Tyler put it).

|

| Nicole Belolan Collection |

As a self-proclaimed heathen, I had never heard of some specimens. Was I really looking at Daniel's encapsulated pulse, as the cover of this better preserved example the National Museum of Play told me?

|

| Sunday-School Teachers' Museum Collected from the Bible Lands, National Museum of Play, 107.3793 |

Yes and no. Pulse is a seed and not just a biological phenomenon. Similarly, circa 1890 children probably were equally unfamiliar with some of the items. Whereas we cook regularly with lentils in our house, they weren't all that common in American kitchens until World War II.

But that's the point of the "Museum." It's an example of an "object lesson." As the leading scholar on the subject Sarah Carter put it, object lessons gave children a way to learn about "the world through their senses, instead of through texts and memorization." Sarah explains that this "lead[] to new modes of classifying and comprehending material evidence drawn from the close study of objects, pictures, and even people."

In this case, Iskiyan and the teachers who used this treasure for teaching deployed it to make the Bible and its message--both of which are some of the least material concepts with which Americans grappled (and continue to do so)--more real to children. Presumably, they hoped spirituality would follow.

Turns our this particular "museum" held shelf space at another popular museum before it found its way to the Allentown Paper Show and into my clutches. I learned from the dealer that when Merritt's Museum of Childhood in Douglassville, PA, (known first as Merritt's Early Americana Museum and then merit's Historical Museum, according to this article) closed its door a few years ago, an auctioneer sold the Sunday School Teacher's Museum along with thousands of other museum artifacts. Sold by Pook and Pook and Noel Barrett, the Museum content ranged from a late nineteenth-century English scale model of a butcher shop ($73,700!) to groups of miniature pewter hollowware.

I got curious about the Butcher shop (what can I say, I like meat), particularly since I guessed (correctly) the "North Carolina Institution" that acquired it was likely the toy museum at Old Salem Museums and Gardens in North Carolina. In the course of googling the Butcher shop (photo below from here)...

...I also learned that Old Salem, which is perhaps best known for its significant collection of Moravian and Southern decorative arts, closed the toy museum in 2010 and sold the collection.

It's striking that Barrett alone has liquidated four toy museum collections. What does that say about our changing interest in learning from traditional toys and play in museum settings?

I'm not sure where the butcher shop is now, but I hope that like my own piece of Merritt's Museum of Childhood History, it's somewhere teaching someone an object lesson.

Sunday, April 19, 2015

Death on the Porch: Uncle Bill Moody's Trophies

Meet Uncle Bill Moody.

Taxidermy is also making a comeback among crafters and DIY-ers. Check out this recent article from the New York Times.

Meet Uncle Bill Moody and his friends.

|

| Nicole Belolan's Collection |

I bought this gem, labeled "Uncle Bill Moody" on the underside, in what looked like an unpromising antique mall in northern Virginia. I was struck by Bill's "here's my stuff" stance and the fact that he and the photographer took the trouble to bring the deer from inside of the house to the porch for the portrait. (As you can see from the detail of the photo below, the taxidermic deer heads would have fallen onto the porch floor if someone had attempted to open a door.)

Bill had this photo taken some time after 1892 and probably before 1910 (his rifle was an 1892 or 1894 Winchester carbine, which I identified using Flayderman's Guide to Antique American Firearms and a little help from Tyler). Around this time, the professional taxidermy trade reached its apex. You can learn more about the history of taxidermy in Beth Fowkes Tobin's "Women, Decorative Arts, and Taxidermy," published in Women and the Material Culture of Death. Yet many forms of the art had preceded this turn-of-the-century manifestation of it. Women had prepared taxidermic animal specimens for decades to make fancywork. Explorers also preserved animals they killed while on exploration expeditions. Many specimens made their way into early museums. And avid hunters like Bill placed them on their walls. If Bill or a family member did the taxidermy work at home, they may have learned how from a book like Practical Taxidermy and Home Decoration (1890). The frontispiece from this book featured a deer much like Bill's and is pictured below.

|

| Practical Taxidermy frontispiece |

Or a professional taxidermist may have processed the heads. It's also possible Bill ordered his trophies "ready-made" from a catalogue like Relics from the Rockies (1894). You can get a sense of the variety of objects Relics peddled from its frontispiece below.

|

| Relics from the Rockies frontispiece |

But based on Bill's photo, I'm inclined to think that he hunted these deer himself and took pride in posing with death on the porch (perhaps carrying on the legacy of displaying "death in the dining room" [to borrow a phrase from one of my favorite books] in the form of sideboards decorated with scenes from the hunt). Either way, this portrait gives us some insight into what Bill's decor looked like inside his home and his standards of gentility. He could have, after all, left his hat inside the house.

Was or is taxidermy a part of your home decor? Let me know in the comments!

Further Reading

For more about the history of taxidermy, see Beth Fowkes Tobin, "Women, Decorative Arts, and Taxidermy," in Women and the Material Culture of Death, ed. Maureen Daley Goggin and Beth Fowkes Tobin (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2013), 311-330.

If you want to take a look at some nineteenth-century taxidermy manuals, you can view many online:

Captain Thomas Brown, The Taxidermists' Manual (1853)

American Mutual Library Association, Ladies' Manual of Art (1887)

H.H. Tammen Company, Relics of the Rockies (1894)

Joseph H. Batty, Practical Taxidermy, and Home Decoration (1890)

Charles Johnson Maynard, Manual of Taxidermy for Amateurs (1901)

Mantague Marks, Home Arts and Crafts (1903)

Captain Thomas Brown, The Taxidermists' Manual (1853)

American Mutual Library Association, Ladies' Manual of Art (1887)

H.H. Tammen Company, Relics of the Rockies (1894)

Joseph H. Batty, Practical Taxidermy, and Home Decoration (1890)

Charles Johnson Maynard, Manual of Taxidermy for Amateurs (1901)

Mantague Marks, Home Arts and Crafts (1903)

Labels:

material culture,

Photography,

taxidermy,

Victorian era

Tuesday, February 3, 2015

Ferdinand (and Rodney) the Bull

Walking toward the exit of the enchanting Pennsylvania Farm Show a few weekends ago, Tyler asked me for a final time whether I wanted to have my photo taken with a Brahman bull.

"No!" I exclaimed, feeling sheepish as young men dressed as cowboys carefully helped toddler-aged girls on and off Rodney's saddle.

What would people think of a grown woman getting up there?

I decided the chances of anyone I know catching me in action were slim, so I relented and proudly marched up to Rodney, mounted his saddle, and smiled broadly.

Within less than a minute, the cowboy handed my photo to me...

...and I handed him $10.

What's funny about this photo (aside from the fact that I got up in the saddle and had it taken) is that a few weeks later, as Tyler and I were going through some antique and vintage photos we had purchased on a recent trip through Virginia, I realized I had forgotten I picked up my circa 1940s twin posed on none other than a touring bull. (I don't know where animal rights' activists fall on this sort of thing, but I can tell you Rodney seemed happy and well fed.)

"No!" I exclaimed, feeling sheepish as young men dressed as cowboys carefully helped toddler-aged girls on and off Rodney's saddle.

What would people think of a grown woman getting up there?

I decided the chances of anyone I know catching me in action were slim, so I relented and proudly marched up to Rodney, mounted his saddle, and smiled broadly.

Within less than a minute, the cowboy handed my photo to me...

...and I handed him $10.

What's funny about this photo (aside from the fact that I got up in the saddle and had it taken) is that a few weeks later, as Tyler and I were going through some antique and vintage photos we had purchased on a recent trip through Virginia, I realized I had forgotten I picked up my circa 1940s twin posed on none other than a touring bull. (I don't know where animal rights' activists fall on this sort of thing, but I can tell you Rodney seemed happy and well fed.)

There are, of course, a few key differences. I did not "ride" side saddle, nor was I handed any faux pistols to "shoot" into the air. Both our bulls have names, but it wasn't until I googled "Ferdinand the Bull" did I learn that Ferdinand the Bull was a popular 1930s book by Munro Leaf about pacifism released shortly before the Spanish Civil War. (You can read a bit more about the book's cultural impact here.)

The book was so popular that even Disney adapted it into a film that won the 1939 Academy Award for Best Short Subject (Cartoon).

So the Ferdinand in my photo may be a live version of (or at least inspired by) the beloved book character. I might never know for sure, as I can't find any other vintage photos of Ferdinand or his bull cousins online. If Ferdinand was a well-known as Wikipedia would have me believe, surely this bull's name would have registered with the young lady forever immortalized in her beach photo.

Did you have your photo taken with Ferdinand, Rodney, or any other Farm Show/Carnival bull? Anyone have a soft spot for this book on their childhood reading list? Let me know about it in the comments!

Further Reading

It's hard to tell from a scan, but these early instant carnival snapshots look a lot like like tintypes in the flesh. In fact, they are not. You can read more about them in a previous post.

Wednesday, January 28, 2015

More on the Makeup Box

Scanning my Twitter feed back in December, I got excited when I spotted what looked like an early twentieth century photograph of a man wearing some dramatic makeup.

I immediately thought of the makeup box I blogged about a few months ago.

Sure enough, the Tweet pointed me toward an excellent blog post about theatrical makeup (and getups meant to evoke specific nationalities or ethnicities) in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The author, Jessica Clark, is a professor of history at Brock University and is working on the early beauty industry (as her faculty profile explains). This is great to know, as I had a difficult time finding a ton of info I could use to figure out what kind of makeup my box contains. Jessica speculated that perhaps the "mystery makeup" is mustache cosmetic. Like any good connoisseur, though, she noted that it's hard to tell without seeing it in person.

Either way, I'm so happy to have learned more about this antiquing find!

Anyone want to do some analytical testing on the box's contents for me?

In the mean time, see you at the paper show in Elton, MD!

I immediately thought of the makeup box I blogged about a few months ago.

Sure enough, the Tweet pointed me toward an excellent blog post about theatrical makeup (and getups meant to evoke specific nationalities or ethnicities) in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The author, Jessica Clark, is a professor of history at Brock University and is working on the early beauty industry (as her faculty profile explains). This is great to know, as I had a difficult time finding a ton of info I could use to figure out what kind of makeup my box contains. Jessica speculated that perhaps the "mystery makeup" is mustache cosmetic. Like any good connoisseur, though, she noted that it's hard to tell without seeing it in person.

Either way, I'm so happy to have learned more about this antiquing find!

Anyone want to do some analytical testing on the box's contents for me?

In the mean time, see you at the paper show in Elton, MD!

Labels:

A.M. Burch & Co.,

acting,

makeup,

material culture,

theater

Monday, January 26, 2015

What a Mess

I love this photograph.

I can't quite make out who and what are pictured in the dozens of photographs arrayed on the wall. But that's besides the point. I love it because I can't help but think about the fact that a hundred years before this late nineteenth-century photograph was taken, it just wasn't possible to surround oneself with likenesses of one's friends and families in this way.

How did photography change the nature of remembering and sentimentality?

How did photography change the nature of remembering and sentimentality?

I also love this photograph because it reminds me how much I wish more curators of period rooms in museums took a cue from "real life" and dared to fashion more cluttered and less sterile (if not physically, than perhaps intellectually) interpretive spaces. A question about how remembering and sentimentality changed over time probably would not be inspired by a period room featuring a token photograph on the wall. Indeed, it occurs to me that most members of the general public (as opposed to a historian/museum pro like me) get their history from house museums, not collecting and studying intently photographs of historic interiors. So it's really up to the keepers of museums to embrace what a mess history was and is and how fascinating and enlightening interrogating these messes can be.

One of the most memorable "messes" I saw in a period room was last winter at Colonial Williamsburg.

For me, at least, I started to think about the history of cleanliness, pest eradication, and even sex--not just the identities of the people who lived there in the colonial era.

So what are we waiting for? Find your museum's mess and stir it up. Or if you are doing this already (or have seen it done), tell me about it in the comments!

So what are we waiting for? Find your museum's mess and stir it up. Or if you are doing this already (or have seen it done), tell me about it in the comments!

Further Reading

I wrote a bit about cleanliness and period rooms last February as it related to workshop period rooms. Check out that post about cleaning, inventorying, cataloguing, and reinstalling a duck decoy shop here.

Kitty Calash writes often and well about accessing "truth," "authenticity," and the like in historical interpretation at living history events and inside historic house museums at her blog, Confessions of a Known Bonnet-Wearer. Franklin Vagnone writes on some of these themes too. You can check out his stuff here.

For more examples of nineteenth-century interiors of people and their photographs, see Katherine C. Grier's Culture & Comfort: People, Parlors, and Upholstery, 1850-1930 (1988).

Labels:

house museum,

Interpretation,

material culture,

museums,

period rooms,

Photography

Tuesday, January 13, 2015

Material Culture Minute: Museum Fabrics to Wear

Last year, I mentioned an article from the 1970s that profiled a woman named Jenny Bell Whyte who made modern clothing out of historic coverlets. She established Museum Fabrics to Wear in 1971, and you can learn more about her philosophy and her craft in the article I have since tracked down thanks to an acquaintance. You can download the article from Americana by clicking here. According to her New York Times obituary, Whyte started making clothing from museum-type artifacts upon purchasing textiles the Brooklyn Museum had deaccessioned and sold at auction in 1975.

Many museum pros would blanch at the practice of making clothing from historic artifacts. But you have to admit, the skirts are fun and probably made from better-quality materials than you can find at most shops today.

I'll let you decide whether to keep your coverlets on your bed or your body!

Many museum pros would blanch at the practice of making clothing from historic artifacts. But you have to admit, the skirts are fun and probably made from better-quality materials than you can find at most shops today.

I'll let you decide whether to keep your coverlets on your bed or your body!

|

| Fashion shot from Jenny Bell Whyte's "Skirts From Coverlets," Americana (September/October 1978) |

Sunday, November 9, 2014

Look, Touch, But You Don't Have to Buy: On Shopping at the Delaware Antiques Show with No Money

Fancy antiques shows like the Winter Antiques Show (benefits East Side House Settlement) in New York City have their critics, but I relish the opportunity to attend such shows. They bring you up close and personal with treasures from America's attics (or dealers' backlog of stock)--in some cases, the likes of which you have never seen and you might never see again (and you can touch, them too!).

With that in mind, let's take a virtual tour of what stood out for me at the Delaware Antiques Show (benefits educational programming at the Winterthur Museum) this past weekend.

In keeping with the feline theme from the last post, check out this family of cats made from discarded socks (probably early twentieth century)...

...and this striking late nineteenth-century painted portrait of a cat.

Peekaboo!

In keeping with the whimsical, here's a great early/mid twentieth-century pediatric dental cabinet.

Couldn't this be repurposed as a jewelry box?

For the Maryland crowd, here's a charming 1860s map (though I must say it looks better in person) of a proposed lumber business for a spot near Port Deposit done on silk. Collector, beware! Silk can be a difficult media for which to care.

And because I cannot help myself, here are my two favorite Berlin work examples from the show. The first, dated 1848, is in impeccable condition. The second, probably from the mid-late nineteenth century, features an original arrangement of a range of Berlin work designs.

Who said all Berlin work was the same?

I'll conclude this tour with a haunting and very unusual painting.

It seems that the portrait was painted around 1800 and that the inscription at bottom noting her passing--"Saturday morning, 5 o'Clock/20th. September, 1817"--was added later.

Wouldn't this be a great centerpiece for a show about mourning and remembrance in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries? Several museum exhibitions showcase mourning as a central theme this season. They look great, but I can't help but be disappointed that mourning exhibitions so often cover the latter half of the nineteenth century. Have any shows featuring that theme attacked an earlier period?

I saw a lot more cool stuff and could go on forever, but I think you get my point. You don't need cash to enjoy these shows - just some curiosity.

With that in mind, let's take a virtual tour of what stood out for me at the Delaware Antiques Show (benefits educational programming at the Winterthur Museum) this past weekend.

In keeping with the feline theme from the last post, check out this family of cats made from discarded socks (probably early twentieth century)...

...and this striking late nineteenth-century painted portrait of a cat.

Peekaboo!

In keeping with the whimsical, here's a great early/mid twentieth-century pediatric dental cabinet.

Couldn't this be repurposed as a jewelry box?

For the Maryland crowd, here's a charming 1860s map (though I must say it looks better in person) of a proposed lumber business for a spot near Port Deposit done on silk. Collector, beware! Silk can be a difficult media for which to care.

And because I cannot help myself, here are my two favorite Berlin work examples from the show. The first, dated 1848, is in impeccable condition. The second, probably from the mid-late nineteenth century, features an original arrangement of a range of Berlin work designs.

Who said all Berlin work was the same?

I'll conclude this tour with a haunting and very unusual painting.

It seems that the portrait was painted around 1800 and that the inscription at bottom noting her passing--"Saturday morning, 5 o'Clock/20th. September, 1817"--was added later.

Wouldn't this be a great centerpiece for a show about mourning and remembrance in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries? Several museum exhibitions showcase mourning as a central theme this season. They look great, but I can't help but be disappointed that mourning exhibitions so often cover the latter half of the nineteenth century. Have any shows featuring that theme attacked an earlier period?

I saw a lot more cool stuff and could go on forever, but I think you get my point. You don't need cash to enjoy these shows - just some curiosity.

Sunday, October 5, 2014

Material Culture Minute: Kittens

While plowing through a new stock of photos at one of our favorite antique malls, Tyler and I came across this stunning tintype portrait of a girl and her kitten.

|

| Tintype of girl and kitten, late nineteenth century (Nicole Belolan's Collection) |

The girl looks self-assured and protective of her little charge. What better way to gain some responsibility as a child--not to mention companionship--than to care for another life? Having just recently cared for a starving mother cat and her four kittens, we immediately connected with this image.

Our "Momma Cat" and her little ones are healthy and happy now. They are living at homes of friends and friends of friends (we were't permitted to keep them where we live). And we hope their new owners are as smitten with them as we were--just as this girl seems to have been too.

Further Reading

For more blogging about the material culture of pet keeping, check out Katherine C. Grier's blog here. She also wrote a book on the subject: Pets in America: A History (2006). Lots of the material for that book (and now the blog) are part of her own collection.

Labels:

animals,

cats,

material culture,

material culture minute,

pet keeping

Wednesday, September 17, 2014

Material Culture Minute: "Are you a doctor?" Or, the Continuing Saga of Collecting Disability History

Combing the aisles of an antique mall in Chadd's Ford, PA, a few weeks ago, I was looking for something special. A friend, who was out and about on a pre-Labor Day 'tique hunt, had just emailed about a mid-late nineteenth-century wheelchair he stumbled across at this mall.

I have plenty of tintypes of people with disabilities, but I am lacking a wheelchair, I thought, and it looked like this one was (to borrow Sandra Lee's phrase) "semi-homemade."

With some extra money burning a hole in my pocket and few encumbrances on that sunny August afternoon, Tyler and I schlepped into Pennsylvania to find the artifact in question.

It didn't take long. We looked it over carefully and were pleased with it overall, but I wasn't happy with the sticker price. Reluctant to ask for a reduction, I nearly walked out and drove home. But thanks to Tyler's encouragement, I found it in myself to demand not the customary 10% discount by rather a whopping 20% discount.

What did I have to loose but a really awesome wheelchair?

To my shock (and the shock of the woman manning the counter), the dealer took my offer. The counter lady walked me back to the chair, slammed her hands on the crest rail, paused, looked at me, and asked in a thick, vaguely New Jersey accent, "What are you going to do with this?"

"Put it inside my office," I declared.

"Are you a doctor?" she asked.

"No. I'm a historian," I said.

"Well, maybe it belonged to FDR," she offered.

"Hm," I muttered, rather ravenous and therefore in no shape to dole out a history lesson.

Instead, I took it home...

Since we have limited space for large pieces of furniture and infinite space for tintypes and crutches, the next big purchase might only be justified if it's a good hundred years older than this puppy. But even then, I'd have a hard time deaccessioning this fascinating piece of the past from my collection.

I've said it before, but I'll say it again. I never thought I'd be one of those people who collects what they study. But there's no going back now, and I wouldn't undo what I've done for the world.

Further Reading

Want to learn more about why I collect the material culture of disability history? Check out my blog post at the Disability and Industrial Society Blog.

Looking for more? On the web, see the Smithsonian's excellent online exhibition EveryBody: An Artifact History of Disability in America.

Finally, if you want to check out a physical book (I can't blame you), see Artificial Parts, Practical Lives: Modern Histories of Prosthetics, edited by Katherine Ott, David Serlin, and Steven Mihm.

Further Reading

Want to learn more about why I collect the material culture of disability history? Check out my blog post at the Disability and Industrial Society Blog.

Looking for more? On the web, see the Smithsonian's excellent online exhibition EveryBody: An Artifact History of Disability in America.

Finally, if you want to check out a physical book (I can't blame you), see Artificial Parts, Practical Lives: Modern Histories of Prosthetics, edited by Katherine Ott, David Serlin, and Steven Mihm.

Sunday, August 10, 2014

It Still Smells like Crayon: On Purchasing a Circa 1890 Makeup Box

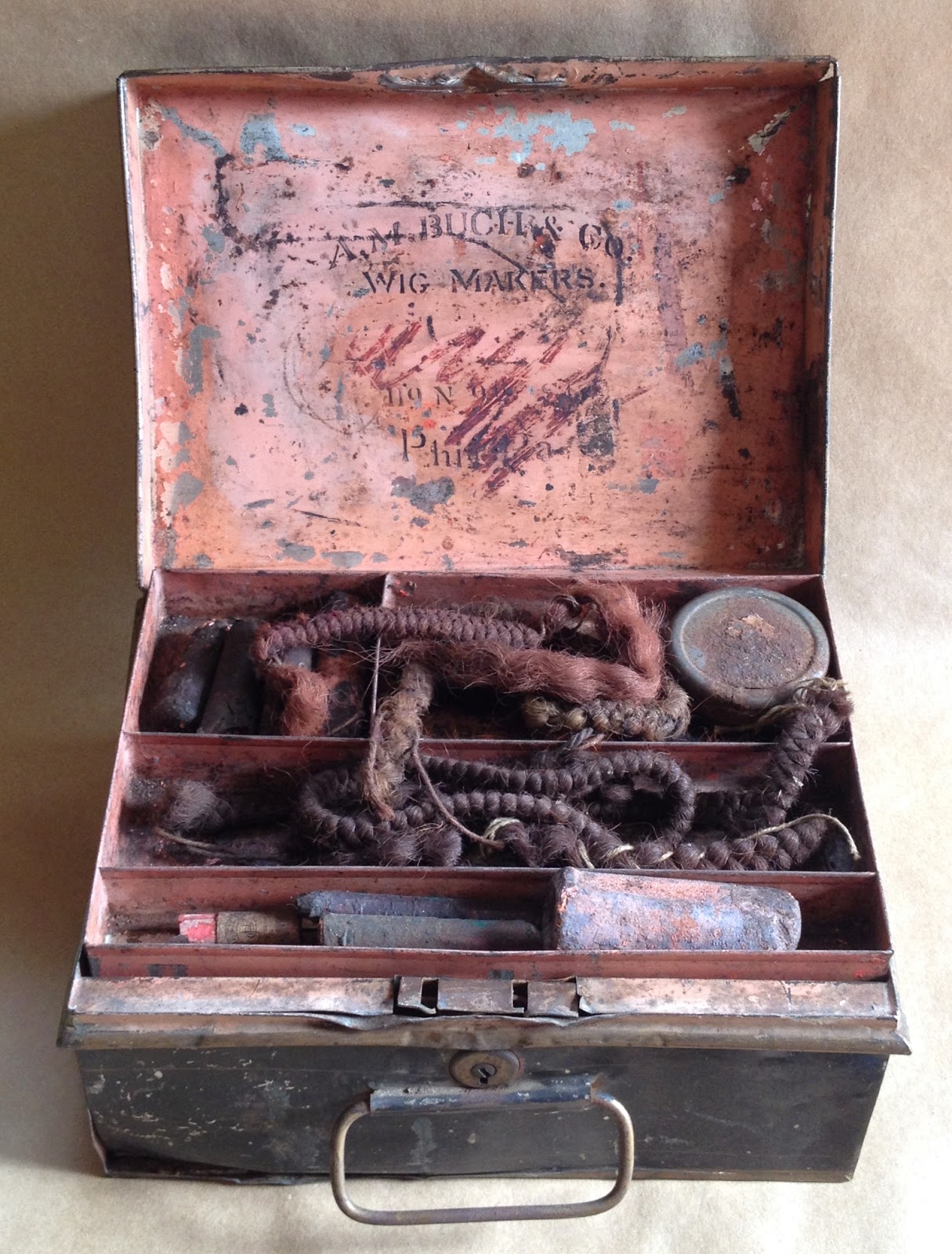

I find it hard to resist antiques I know probably should have been discarded years ago. The best example I have of that is this late nineteenth-century makeup box, which I acquired back in 2010.

It seems like a lot of that is still in there, including grease paint (see sticks), not the mention a strong crayon odor.

I can't tell for certain what's inside each of the tins. Some tins that remain inside this box are empty, others contain black lumps of mystery makeup.

Grease paint, it seems, became widely available by the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Until then, according to James Young's 1905 publication Making Up, actors used relatively little makeup. Or, perhaps more likely, they made their own greasy goo. Once someone found a way to produce grease paint on a large scale, the industry took off. The rise of grease paint spurred a flurry of turn-of-the-century how-to manuals on applying makeup (with an emphasis on grease paint) for the stage. According to Young, grease paint facilitated actors' being "real...even in the unreality of the supernatural." New stage lighting techniques may have illuminated actors' faces better, requiring heavier makeup such as grease paint to make the actors appear physically more "in character."

Another handbook, Charles Harrison's 1882 Theatricals and Tableaus Vivants for Amateurs, noted that, after the mid-nineteenth century, more and more plays featured contemporary characters. Makeup, therefore, became a more important part of the costume when the actor could not rely on recognizable historic-looking objects to represent specific historical figures (pirates, soldiers, prostitutes, etc.). As a result, making-up manuals and makeup trade catalogues, which seem to cater to amateur actors in particular (though not exclusively), emphasized creating the "right" skin shades or marks of age. Whether or not this was all true is unclear, but these writers and makeup manufacturers were certainly good marketers!

Back in 2010, I hemmed and hawed about whether or not to snatch this up. What would I do with rotting stage makeup? The box sits silent and shut on a shelf in my office, but it has character, and it evokes a good time. It's also a good artifact to use for care and handling training. (In this case, be sure to wear gloves when handing unknown substances!) Back in 1890, Burch advertised it as his "special" makeup box. It's now my special makeup box, dirt, grease, and all.

What else can I ask for in an antique?

When I first made this purchase, I promised you all I'd blog about a mystery object in "the coming weeks." It looks like I meant "coming years," as I'm just getting to this now. I hope it was worth the wait.

Anyone have any late nineteenth-century stage makeup ephemera out there? I'd love to learn more about collecting historic theatrical makeup!

|

| "Our Special Make-up Box," Circa 1890 Stenciled label reads: A.M. Buch & Co./WIG MAKERS./119 N. 9th Street/PHILADELPHIA |

This gem was made by A. M. Burch & Co., based at 119 N. 9th Street in Philadelphia. Described as "Our Special Make-up Box" in its 1890 trade catalogue I read thanks to The Athenaeum of Philadelphia, the original would have come stocked with the following:

"Heavy Black Tin, with tray, separate compartments, with Yale Lock and two keys. 70 cents a piece. The Actor's Make-up Box. A handsome decorated tin case containing the various article commonly used in 'making up' for the stage; will answer all ordinary requirements of any actor. It contains a set of Face Paints (9 colors) Light Flesh and Dark Flesh Face Powder. Powder-puffs, Hares foot, Cold Cream, Dry Rouge, Nose Putty, Grenadine Lip Rouge, Spirit Gum; Moustache Cosmetique; Black Wax, 2 camel's hair pencil's, 2 shades of Water Cosmetique, a light and a dark, with a brush for applying them. Mirror, scissors and an assortment of crepe hair. Price complete $4.00."

|

| Contents of wig box bottom |

|

| Assorted wig box contents |

I can't tell for certain what's inside each of the tins. Some tins that remain inside this box are empty, others contain black lumps of mystery makeup.

Another handbook, Charles Harrison's 1882 Theatricals and Tableaus Vivants for Amateurs, noted that, after the mid-nineteenth century, more and more plays featured contemporary characters. Makeup, therefore, became a more important part of the costume when the actor could not rely on recognizable historic-looking objects to represent specific historical figures (pirates, soldiers, prostitutes, etc.). As a result, making-up manuals and makeup trade catalogues, which seem to cater to amateur actors in particular (though not exclusively), emphasized creating the "right" skin shades or marks of age. Whether or not this was all true is unclear, but these writers and makeup manufacturers were certainly good marketers!

|

| "Conventional Types," from James Young, Making Up (1905) |

Back in 2010, I hemmed and hawed about whether or not to snatch this up. What would I do with rotting stage makeup? The box sits silent and shut on a shelf in my office, but it has character, and it evokes a good time. It's also a good artifact to use for care and handling training. (In this case, be sure to wear gloves when handing unknown substances!) Back in 1890, Burch advertised it as his "special" makeup box. It's now my special makeup box, dirt, grease, and all.

What else can I ask for in an antique?

When I first made this purchase, I promised you all I'd blog about a mystery object in "the coming weeks." It looks like I meant "coming years," as I'm just getting to this now. I hope it was worth the wait.

Anyone have any late nineteenth-century stage makeup ephemera out there? I'd love to learn more about collecting historic theatrical makeup!

Wednesday, June 11, 2014

A New Blog

|

| In this snapshot (a recent acquisition-isn't it a great interior?), it looks like our friend has an announcement to make! |

I started the blog off with a post on figuring out where General Howe landed his troops in present-day Maryland back in 1777 ahead of the American Revolution's Philadelphia Campaign (more interesting than it sounds!) and another post on the recent demolition of Delaware's 1760 Kux-Alrich house.

Let me know what you think!

You can make following easier by becoming an email subscriber or by adding the blog's address to a blog reader or news aggregator like Feedly.

And yes, there's another antiquing blog post in the works about something grimy but fascinating.

How's that for a teaser?

Labels:

blogging,

General Howe,

Kux House,

material culture,

museums,

outreach,

research,

teaching

Friday, May 30, 2014

Material Culture Minute: "We Go from One Thing to Another"

There is often a fine line between what antique dealers sell and what they collect. In some cases, dealers display their personal collections inside their shops. And why not? They give patrons something else to look at, and the collection doesn't (as far as we know) take up valuable space inside the dealer's home.

Tyler and I recently encountered an impressive dealer collection at an antique store in Maryland. As we walked around the shop, we admired the hundreds of items the dealer had in his collection. We didn't need to ask about the collection ourselves to learn more about it, though. A regular beat us to it. In response, a store clerk explained:

Store clerk: "Well, Alfred's been buying oyster cans. You can see he's got them lined up there along the ceiling. He's really into them right now. We go from one thing to another."

Regular store patron: "Oh, I like them oyster crocks. Even seen them oyster crocks?"

Store clerk: "Oh, yeah, they're pretty nice. We just bought one the other day for $2,500."

Sure, that's a lot of of money. But many food containers (or advertising items, including stoneware crocks) weren't meant to or expected to last long. So I'm not surprised the market supports premium prices for items that would have been considered disposable or not long for this world when they were first used.

It's hard to say what this dealer's next thing will be. In the mean time, I'll keep an eye out for one of them oyster crocks.

Tyler and I recently encountered an impressive dealer collection at an antique store in Maryland. As we walked around the shop, we admired the hundreds of items the dealer had in his collection. We didn't need to ask about the collection ourselves to learn more about it, though. A regular beat us to it. In response, a store clerk explained:

Store clerk: "Well, Alfred's been buying oyster cans. You can see he's got them lined up there along the ceiling. He's really into them right now. We go from one thing to another."

|

| Many of the oyster tins on display inside this antique shop looked like this beauty. On the reverse, the can assures customers that its contents are safe for consumption. Oyster packagers added such labels when the federal government enhanced its food safety laws around 1900. Legislators crafted many of these laws in response to a variety of food-related dangers that developed as the food processing industry expanded with little oversight and consumers were less and less likely to buy their food from the source (or a local middle man). In the case of oysters, deadly cases of typhoid fever (caused by salmonella) had been linked to the mollusk. Oyster tin, Pride of the Chesapeake brand, 1920s, 7.25" x 6.56," 2007.0054.01 (Smithsonian) |

Regular store patron: "Oh, I like them oyster crocks. Even seen them oyster crocks?"

Store clerk: "Oh, yeah, they're pretty nice. We just bought one the other day for $2,500."

Sure, that's a lot of of money. But many food containers (or advertising items, including stoneware crocks) weren't meant to or expected to last long. So I'm not surprised the market supports premium prices for items that would have been considered disposable or not long for this world when they were first used.

|

| Perhaps the "new" crock looks something like this one, sold recently at Crocker Farm Auction for $345. According to Crocker Farm, the five gallon crock dates to about 1880 and is likely from Ohio. It is marked: “A. BOOTHS SOLID MEAT OYSTERS." |

It's hard to say what this dealer's next thing will be. In the mean time, I'll keep an eye out for one of them oyster crocks.

Sunday, April 27, 2014

Stocking Up

It's a real pleasure to receive an invitation to lecture on my M.A. thesis topic--Berlin work--five years after I finished that degree and three years after publishing an article based on that research. I must admit that I had that Spring 2015 lecture in mind upon purchasing Elizabeth Gotvals's 1847 sampler at my favorite antique shop near in Pennsylvania last weekend.

Wow, an identified and dated piece of Berlin work, made when Americans had only begun to embrace the needlework made using soft woolen threads and patterns printed in women's magazines and sold by the piece in fancy shops. I'm not sure if the backing is lignin-free and acid-free, so I'll probably carefully switch it out with something I can confirm is inert and therefore less likely to speed the sampler's inevitable deterioration. That said, it's in pretty good condition. I am simply thrilled to add this to my collection. But, frankly, it's always a good day when I have an opportunity to stock up on Berlin work specimens I can trot out for my lecture audiences (not to mention my students). Nothing beats learning from the objects themselves.

So what do we have here?

Elizabeth's work includes a traditional "sampler" design at the top featuring the alphabet and numerals in silk on plain-woven cotton canvas. The bottom portion features Berlin work designs (mostly floral) in wool. As I have explained before, needlework collectors tend to shy away from this stuff for a few reasons. Many people think it's 1) unoriginal and 2) gaudy. The wool's colors are too bright and therefore tasteless, some think. Critics also believe that the Berlin needlework designs, wrought using widely disseminated patterns as guides, embodies a lack or imagination on the part of the needleworkers.

I'll leave it up to you do decide for yourself how you feel about it.

In the mean time, I'll keep collecting it and lecturing about it.

Further Reading

For more about Berlin Work, see my article in Winterthur Portfolio: "'The Blood of Murdered Time': Ann Warder's Berlin Wool Work 1840-1865," Winterthur Portfolio 45, 4 (Winter 2011): 321-352.

I have also written about Berlin work on this blog before. Check out this post, "Berlin work: craft, kitsch, and fashion."

Berlin Work in Museums

In my region, some of my favorite Berlin work can be found at the Winterthur Museum and the Schwenkfelder Library and Heritage Center.

Wow, an identified and dated piece of Berlin work, made when Americans had only begun to embrace the needlework made using soft woolen threads and patterns printed in women's magazines and sold by the piece in fancy shops. I'm not sure if the backing is lignin-free and acid-free, so I'll probably carefully switch it out with something I can confirm is inert and therefore less likely to speed the sampler's inevitable deterioration. That said, it's in pretty good condition. I am simply thrilled to add this to my collection. But, frankly, it's always a good day when I have an opportunity to stock up on Berlin work specimens I can trot out for my lecture audiences (not to mention my students). Nothing beats learning from the objects themselves.

So what do we have here?

Elizabeth's work includes a traditional "sampler" design at the top featuring the alphabet and numerals in silk on plain-woven cotton canvas. The bottom portion features Berlin work designs (mostly floral) in wool. As I have explained before, needlework collectors tend to shy away from this stuff for a few reasons. Many people think it's 1) unoriginal and 2) gaudy. The wool's colors are too bright and therefore tasteless, some think. Critics also believe that the Berlin needlework designs, wrought using widely disseminated patterns as guides, embodies a lack or imagination on the part of the needleworkers.

I'll leave it up to you do decide for yourself how you feel about it.

In the mean time, I'll keep collecting it and lecturing about it.

Further Reading

For more about Berlin Work, see my article in Winterthur Portfolio: "'The Blood of Murdered Time': Ann Warder's Berlin Wool Work 1840-1865," Winterthur Portfolio 45, 4 (Winter 2011): 321-352.

I have also written about Berlin work on this blog before. Check out this post, "Berlin work: craft, kitsch, and fashion."

Berlin Work in Museums

In my region, some of my favorite Berlin work can be found at the Winterthur Museum and the Schwenkfelder Library and Heritage Center.

Friday, March 7, 2014

Stuck Between a Decoy and some Berlin Work

|

| Norman Rockwell's Good Friends (1925) & #UDFlat_SPencer |

What did we find?

About five minutes into the visit, I spotted some ice fishing decoys similar to these beauties at the American Folk Art Museum. On one, priced at $85, the fins had been made using recycled news- or magazine-print. How charming, I thought. It reminded me of the make-do spirit embodied in many of the artifacts at the Upper Bay Museum in North East, Maryland.

|

| Horace Graham's (active 1955-1978) auto-sander made with a washing machine motor at the Upper Bay Museum |

Tempting!

But a mere five minutes later, I spotted a large framed piece of Berlin work (a type of wool on cotton canvas pictorial fancy needlework popular in the mid nineteenth century) in the next room and made a beeline for it. At right, check out an example of Berlin work, which, as it turns out, I acquired from the same antique mall about a year ago. Tyler helped me get the prospective purchase off the wall but not without knocking down its hook in the process. An eagle-eyed co-op worker happened to be walking by. We apologized, and she told us not to worry about the casualty. But then proceeded to stand next to me pretending to be reading some paperwork while I examined the piece.

Like the one I bought a year ago, the prospective acquisition had provenance, and the price was right. (I have found that the pictorials, often featuring a scene and perhaps a name, call for less than do the sampler-style Berlin work, often featuring images as well as names, dates, and perhaps letters or numbers.) It had a lot going for it. But I am trying to save some pennies for a variety of things ranging from groceries to a 2015 tour of Waterloo and its environs.

So after carefully setting the needlework against a wall, we did a loop of the rest of the co-op. I saw a few more decoys--once you work with something, you see it everywhere--but none that I found to be particularly beguiling. In my travels, I've seen duck decoys range in price from under $100 to several hundred dollars. If you follow that market at all, you know they can fetch tens of thousands. Once a utilitarian, everyday item used not alone but in groups of tens or perhaps a hundred, after the decline of market duck hunting in the early twentieth century and then the transition to plastic decoys in the mid-century, duck decoys skyrocketed in "folk art" and monetary value. And so with the death of the wooden decoy came the renaissance of decoy-carving and the start of the collecting fever.

Thus far, I have kept the miasma at bay.

|

| As predicted (and widely feared) it snowed Monday, March 3. |

And once she buys the rack, she still needs some money left over to paint it.

"You're going to paint it?," the worker asked.

"Yes," responded the buyer.

"Oh...dear," the worker exclaimed, unable to hide her dismay and disgust.

Just as breathing down someone's neck while they take a look at a piece of needlework isn't the best way to sway an interested buyer, neither is chastising someone's plans to "deface" an anonymous piece of metal.

|

| Coverlet, wool & cotton, America, 1825 Metropolitan Museum of Art, 10.125.410 |

With the 'tique desecration exchange humming in the background, I hemmed and hawed for a few more minutes over the Berlin work. With dreams of Waterloo dancing in my head, at last, I decided we should head to Whole Foods. There, we chattered about living in a world where we can buy (but did not) $6.99 jars of "organic," "undyed" maraschino cherries at a place that employs guys to stand behind a fish counter wearing overalls in an effort to create the illusion that the workers are fresh off the docks.

I wonder if they know what ice fishing decoys look like.

Want to Learn More?

There are some good web sites that address decoy collecting. Check out the Collectors Weekly site on "Vintage and Antique Duck Decoys." Their interview with a decoy collector is also informative; it mentions several antiquarian books that would be of interest if you want to learn more about identifying decoys if you're on the hunt.

In preparing for my work at the Upper Bay Museum, I found that C. John Sullivan's Waterfowling on the Chesapeake, 1819-1936 (2003) provides readers with the best historical context for duck decoy use. Those with a theoretical bent might enjoy Marjolein Efting Dijkstra's The Animal Substitute: An Ethnological Perspective on the Origin of Image-Making and Art (2010).

Finally, if you hunger for more information on Berlin work, check out my article "'The Blood of Murdered Time': Ann Warder's Berlin Wool Work, 1840-1865," in Winterthur Portfolio.

Want to Learn More?

There are some good web sites that address decoy collecting. Check out the Collectors Weekly site on "Vintage and Antique Duck Decoys." Their interview with a decoy collector is also informative; it mentions several antiquarian books that would be of interest if you want to learn more about identifying decoys if you're on the hunt.

In preparing for my work at the Upper Bay Museum, I found that C. John Sullivan's Waterfowling on the Chesapeake, 1819-1936 (2003) provides readers with the best historical context for duck decoy use. Those with a theoretical bent might enjoy Marjolein Efting Dijkstra's The Animal Substitute: An Ethnological Perspective on the Origin of Image-Making and Art (2010).

Finally, if you hunger for more information on Berlin work, check out my article "'The Blood of Murdered Time': Ann Warder's Berlin Wool Work, 1840-1865," in Winterthur Portfolio.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)