We had joked with friends about my chances of winning the door prize for a second time, but I had never expected that it might actually happen. I don't plan on sharing the booty, but I will take a few moments to share some recent paper and photographic acquisitions with you.

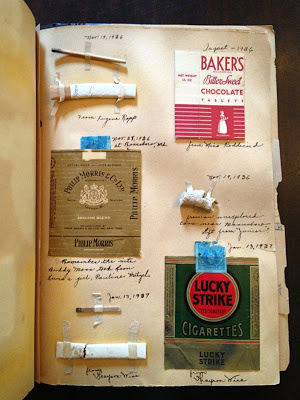

First, there's the item I bought at the January paper show: a 1930s scrapbook a teenager in high school put together. I tweeted a teaser photo a few weeks ago, and I hope to blog about it soon when I have more time to take a closer look at it. (For starters, she liked to save cigarettes.)

I can't emphasize enough how much I enjoy collecting paper ephemera and photographs. For one, these objects are accessible to most people (including kids--start 'em young!) in terms of cost. Saturday, for example, I bought several photos for just $2/each at the Elkton Antique Show (same location as the paper show). Second, this stuff is portable and is great to collect for teaching purposes. When I want to bring a real mid-ninteenth-century religious tract into class to show students what tract society peddlers carted around to promote developing a more personal relationship with God, I can. I have two stored safely in acid-free plastic sleeves.

What else have I acquired recently? For starters, I am a sucker for unusual or hard-to-find photographs of interiors or exteriors that document everyday and ordinary domestic life. We know how the elites lived. Their stuff is published, collected, and interpreted with verve. We know less about how ordinary folk lived. Take, for instance my friend Mr. Grier Youngman here (he name is on the underside). At first glance, I registered a regular guy reading, sitting in a common Victorian balloon-back chair. As I looked a few seconds more, I noticed all the "props" in this photo that give us some hints into his everyday life. He rode a bike, which is peaking out from behind the chair and the packed rotating bookshelf. On the wall, you see two decorative pieces of art and what is most likely the bottom of an American flag.

What else have I acquired recently? For starters, I am a sucker for unusual or hard-to-find photographs of interiors or exteriors that document everyday and ordinary domestic life. We know how the elites lived. Their stuff is published, collected, and interpreted with verve. We know less about how ordinary folk lived. Take, for instance my friend Mr. Grier Youngman here (he name is on the underside). At first glance, I registered a regular guy reading, sitting in a common Victorian balloon-back chair. As I looked a few seconds more, I noticed all the "props" in this photo that give us some hints into his everyday life. He rode a bike, which is peaking out from behind the chair and the packed rotating bookshelf. On the wall, you see two decorative pieces of art and what is most likely the bottom of an American flag.

What's his story? Perhaps this gentleman boarded in a room alone, and perhaps he made a living in a profession that required a small library. Or he was a voracious reader. In either scenario, he probably featured his books (and his reading) prominently in this photograph because he saw his books as part of his identity. After doing some genealogical digging in Ancestry Library Edition, I discovered that Grier was from Danville, PA, and that he was born around 1871. He married in 1894, and I would suspect that he had this photo taken when he was still a bachelor bank cashier (or teller). The way Grier staged this photograph suggests that he had some professional ambitions as a young man. And so it is not surprising that, by the time 1930 rolled around, according to the census, Grier had become the President of the Danville National Bank. Grier had built what we might consider a solidly "middle class" lifestyle by the Depression. Did this photograph represent Grier's aspirations to attain that status? What made the interior we see here a "home" for him?

Exterior visions of domestic life can be equally thought-provoking.

In this photo, we see (cut?) flowers sitting on a shelf at right, as well as some hanging flowers descending from the roofline. Presumably, early twentieth-century ordinary folk used plants and flowers for decorative purposes around their homes, but we rarely see that practice documented in photographs (let alone in manuscript evidence). And by chance, it looks like I might have found a photograph featuring an older man with a cast of his left hand (related to my interests in disability history). What do you think?

Also with the body in mind, take a look at this photo.

Also with the body in mind, take a look at this photo.

We don't think much of women drawing attention to their pregnancies in photographs today. Indeed, celebrities often pose nude when pregnant for magazine covers. Did you ever stop to think when it became customary to draw attention to one's pregnancy while posing for a photograph (or any portrait, for that matter)? It looks like that might be what is going on in this early twentieth-century image.

I am unaware of a tradition of "pregnancy" portraiture in early American visual culture. That said, I do know that a number of Elizabethan era portraits picturing women in the late stages of pregnancy survive. Scholars such as Karen Hearn and Pauline Croft have suggested that those

portraits, an example of which you can see below, may have embodied, among other things, concerns over political machinations, producing successors to various hereditary titles, and the health dangers associated with bearing children as women aged.

|

| Portrait of a woman, probably Catherine Carey, Lady Knollys, oil on panel, 1562 (Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection). Published in Pauline Croft and Karen Hearn, "'Only matrimony maketh children to certain...' Two Elizabethan pregnancy portraits," The British Art Journal 3, 3 (Autumn 2002): 20. |

And finally, we have some jokesters.

I bought this online for Tyler for Christmas, thinking it was a whimsical tintype (as the dealer said it was).

I was somewhat skeptical since the men's hairstyles looked to be from the 1920s, but I knew that tintypes were (believe it or not) in use through the 1930s.

Sure enough, when I opened the package, I knew the minute I looked at the photograph in person that it was not, in fact, a tintype but a paper photograph that looks a lot like a tintype when developed. I am not annoyed that I didn't receive a tintype. Rather, I am annoyed I have yet to figure out exactly how this photograph was produced. I think it may be an example of a photograph produced by a an early photobooth or photomaton that was used to capture images of people at fairs and carnivals. In the cop and robber photo, for instance, the fact that there appears to be a crowd in the background suggests that this was taken outdoors at a place (such as a fair or carnival) where there would have been a lot of people. If anyone out there is familiar with such images from the early twentieth century, I'd be interested to learn more about them. What can this practice reveal about how the conventions of humor and visual trickery have changed over time?

Once I had familiarized myself with "fair" photos, I didn't hesitate for an instant to snatch up this contemporaneous photo of a man posing behind a "fat suit" cutout.

Once I had familiarized myself with "fair" photos, I didn't hesitate for an instant to snatch up this contemporaneous photo of a man posing behind a "fat suit" cutout.French fries, anyone?

Further Reading

Historians, sociologists, and economists alike have

On the history of Mr. Youngman's bicycle, see David V. Herlihy, The Bicycle (2004).

For more on Elizabethan pregnancy portraits, see Pauline Croft and Karen Hearn, "'Only matrimony maketh children to certain...' Two Elizabethan pregnancy portraits," The British Art Journal 3, 3 (Autumn 2002): 19-24.

Humor, visual trickery, and photographic manipulation boast long histories. You might be interested in the Met's recent exhibition on the history of photographic manipulation. On of the exhibition's sub themes was "novelties and amusements." In addition, Tromp l'oeil ("to fool the eye") visual culture in American isn't quite analogous to what we're seeing in the fair and carnival snapshots above, but I think it's related. If you're interested in reading more about visual trickery and the tradition of tromp l'oeil (to fool the eye) painting in America, see Wendy Bellion's Citizen Spectator: Art, Illusion, and Visual Perception in Early National America (2011), exhibition highlights from the National Gallery of Art's exhibition Deceptions and Illusions: Five Centuries of Tromp L'oeil Painting, and the online catalogue for the Brandywine River Museum's exhibition on contemporary tromp l'oeil artists here.

No comments:

Post a Comment