bought a blank scrapbook.

...to dance cards and bows.

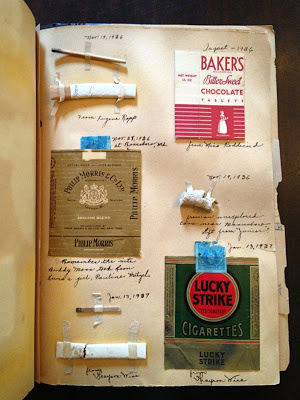

In 2013, I bought Virginia's scrapbook at one if my favorite paper shows: the Paper Americana Show in Elkton, MD.

I have nothing that compares to Virginia's scrapbook. At various times during my life, I did make a few scrapbooks of my own. I discarded most of them in one of many fits of unburdening myself of unnecessary stuff. Just think how many more scrapbooks we might have today if people like me had never, as some people put it, decluttered. Or, consider how many fewer scrapbooks we will have from our times since so many people are "going paperless." Yes, the paper scrapbooking industry--while still strong--is in decline, as some are reporting.

Like many scrapbooks, Virginia's includes lots of stuff we would consider ephemeral. In other words, when most people finished eating their Planters Peanuts in 1935, they discarded the wrapper.

Let's face it. There aren't many of us out there saving our receipts, food containers, or our bookmarks, either casually or methodically (like Virginia). As Tyler and I walked around the Paper Americana Show this past January, we mused about how much longer we'd have piles of early twentieth-century snapshots to wade through at paper shows. Today, many stores email receipts, and most of us squirrel away our photographs in "the cloud." Someone better be saving this stuff so future collectors have something to buy at the Paper show that isn't on an external hard drive, we decided. I started to wonder what a day's worth of my discardable paper might mean to a paper show patron in 2064.

So in the space of about twenty-four hours, I did not throw away (or recycle) my paper and other ephemeral waste--a sort of experimental archaeology exercise that gave me a chance to think about my habits as they related to the stuff we casually toss away today.

At the end of the day, I piled up everything from candy cigarette boxes to Colonial Williamsburg Foundation membership offers...

...from interlibrary loan slips to credit card junk mail.

I learned more about myself and the world and then I thought I would. One of the things I noticed was my near automatic impulse to throw away my parking garage receipt and other pieces of the day immediately upon removing the coat in which I had temporarily stashed them for the short ride home. I also noticed that when it came to "junk mail," I didn't even bother opening most of it. I also didn't bother to expunge my name from the various marketing mailing lists on which my name appears. (So I will be receiving these things in perpetuity.) The only reason I opened the Colonial Williamsburg offer is because I wanted to photograph (for the blog) the Foundation membership card I knew they included inside the mailing based on nearly identical promotional material I had already received. (Don't get me wrong - I do love Colonial Williamsburg). I also decided (and this isn't all that revolutionary) that we just generate more paper than seems to be necessary. The book I interlibrary loaned (using an electronic form) generated at least one and half pieces of full-sized paper. When will this "paperwork" be completely digital (let alone--gasp--the book itself)? And once I sat down to a meal, it occurred to me that my little experiment excluded food packaging (save the candy container) and toiletry packaging entirely. But I can tell you that I use shampoo, split end repair and four facial cleansers and creams on a regular basis...all of which I purchase along with disposable containers. I considered my body routine to be relatively low-maintenance until I started tabulating the damages. Finally, after I snipped a piece of red ribbon from the bouquet Tyler got me, I thought about all the stuff around me (health records, miscellaneous school papers, birthday cards...) that will, within a matter of a few months or perhaps a few years, be discarded. Do I live among trash?

I will live among more soon. I cooked up the scheme that I will save my paper ephemera one day every year until I no longer have any junk mail or ILL slips to save. I hope my students will appreciate the opportunity to think about change over time as it applies to my paper.*

When I sell my "ephemeral Property of Nicole Belolan" collection or show it to my students, some will giggle at how quaint those physical credit cards were back in the old days. They may even pause for a moment in disbelief as they try to figure out if the eighteenth-century looking newsprint, which you can buy readily at Colonial Williamsburg, is really from "early" America. (I won't speculate here when will we be teaching "later" America or twenty-first century America. Perhaps we already are.)

Just like I will continue to wonder why Virginia saved cigarettes boys (suitors?) gave her, perhaps in 2064 someone will puzzle over why the same person who interlibrary loaned historical monographs about early American disease also consumed candy cigarettes.

* Interestingly, I converted to Apple's iCal about two years ago and just this January went back to my paper system. Somehow I feel more in control of my time when I mark it with paper.

Further Reading

I've been meaning to write this post for a while now, but I was newly inspired to put fingertips to keyboard by my dissertation adviser's current grad seminar about disposability (sadly, I am no longer in coursework!) and this TeachArchives.org exercise titled "Digging for Garbage in the Archive."

For more on the history of hobbies and do-it-yourself culture, see “Introduction: Context and Theory,” in Steven M. Gelber, Hobbies: Leisure and the Culture of Work in America (1999): 1-20. I don't necessarily agree with the suggestion that hobbies are a postindustrial phenomenon, but this is a landmark book, nevertheless.

If you want to read more about scrapbooking and the history of similar paper crafts, see Beverly Gordon, The Meaning of the Saturated World and “The

Paper Doll House,” in The Saturated World: Aesthetic Meaning, Intimate Objects, Women’s Lives, 1890-1940 (2006):

1-35 and 37-61,

And finally, if you want to read more about ephemeral material culture, check out Maurice Rickards and Michael Twyman, Encyclopedia of Ephemera (2000), William Davis King, Collections of Nothing (2009), Susan Strasser, Waste and Want: A Social History of Trash (2000), and Joseph Heathcott, "Reading the Accidental Archive: Architecture, Ephemera, and Landscape as Evidence of an Urban Public Culture," Winterthur Portfolio 41, 3 (Winter 2007): 239-268.