-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Most recently, I talked about my research as part of a seminar called "

Fashion and Fiber: Reimagining the Sources and Use of Textiles" offered at the University of Delaware this semester. The audience was composed primarily of undergraduates studying fashion in addition to others who are pursuing a minor in material culture. There were also a few community members in the audience, not to mention a few supportive colleagues. No matter how much I prepare for such a presentation, I always fear that perhaps my angle will miss the mark. Luckily, it seems that opening with a discussion of a November 2008

Elle fashion spread generated enough interest to sustain a great post-presentation conversation.

The fashion spread reads: "The Season's Homespun Needlepoints and Crochets Offer Equal Parts Kitsch and Comfort."

1 The spread pictures an array of clothing and accessories that were made using a form of needlework (such as knitting, crocheting, or needlepoint) or clothing and accessories that are adorned with motifs that evoke needlework. Technical points aside (needlework cannot be "homespun" since, by definition, it is not woven in the first place),

Elle invites readers to buy, wear, and gift something that looks to be homemade. Simultaneously, the spread denigrates needlework by calling it "kitsch." No matter how "couture" needlework has become, it cannot escape its critics. This discourse reflects ongoing debate over needlework and its meaning.

The presentation outlined how I came to study Berlin work; the depth of the collection that served as my case study; the nature of Berlin work; the history of Berlin work criticism; and what this case study tells us about Berlin work that was not known previously. Finally, the point of including the

Elle fashion spread was to think about how Berlin work fits into contemporary notions of craft and fashion.

The thesis was inspired by a collection of Berlin work patterns and Berlin work fragments made, altered, and owned by Ann Warder (1824-1866) of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

2 The collection also includes Warder's knitting receipt (or instruction) book, her 1832 marking sampler, an eighteenth-century family needlework book cover, a circa 1820 family needlebook, and a circa 1800 family chatelaine. (See this

brief article I wrote for the Decorative Arts Trust when I was only beginning my thesis research. It's great for images of the collection and Ann Warder.) Using this collection, which is part of the

Winterthur Museum's collection of textiles and needlework, Warder's extant papers (mostly at

Haverford College Library), and nineteenth-century Berlin work print culture, I examined how one woman's execution of Berlin work helped us understand Berlin work materials and how they related to other nineteenth-century needlework materials; how Berlin work served as a past time and a way to develop and maintain familial relationships; and how these materials, function, and meaning show continuity as well as discontinuity with previous needlework practices.

Here are some highlights:

Berlin work is a type of wool on canvas or perforated cardboard fancy pictorial needlework that was most popular in the United States between 1840 and 1880. The wool tends to be 4 ply, S twist, Z spun woolen zephyr merino yarn, although there were variations I document in my thesis.

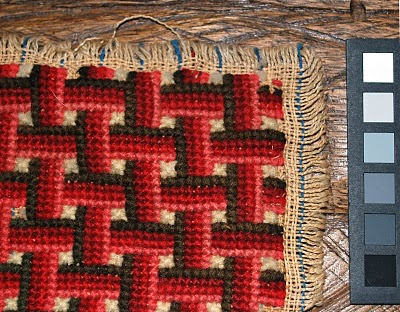

This detail of a Berlin work mat should give you a good idea as to what Berlin work yarns look like up close. I purchased the mid nineteenth-century Berlin work mat for a few dollars at a tag sale a few months ago.

Berlin work designs were published as patterns that were sold in portfolio form or in popular women's magazines. The earlier, European-made patterns tended to be engraved and hand-colored. The later American patterns tended to be lithographed and printed in magazines. I purchased this booklet of small Berlin work patterns at an ephemera sale last spring for $30. It probably dates to the 1850s or so. Small patterns like these were used in conjunction with other motifs on samplers, and they were also added to embellish other projects.

Like needlework that preceded it, Berlin work was made for pleasure, profit,

education, and kinship-building; Berlin work was made into objects ranging from samplers to seat covers to book covers to portraits.

This pair of Berlin work slippers was made between 1830 and 1850 in England. Given by Messrs. Harrods, Victoria & Albert Museum, London, T.587 to A-1913.

This pair of Berlin work slippers was made between 1830 and 1850 in England. Given by Messrs. Harrods, Victoria & Albert Museum, London, T.587 to A-1913.

To my delight, one of the first objects upon which I laid my eyes at the same ephemera show where I purchased the pattern booklet picture above was this book cover. Having completed a research project on needlework book covers (mostly eighteenth-century, although a few nineteenth-century covers made using Berlin wool) while I was studying at Winterthur, I was thrilled to see a Berlin work on perforated cardboard example. This particular cover may have covered a personal keepsake album, but I suspect that is was made to cover a nineteenth-century gift book published under the title

Tokens of Remembrance.

Like needlework that came before it, Berlin work was criticized. This criticism is important to understanding the needlework today because it suggests some reasons as to why Berlin work was maligned for so long. These criticisms ranged from issues with aesthetics to objections to the way women used their time. Berlin needleworkers were aware of such objections. Warder herself copied an oft-cited poem bemoaning Berlin work in one of her copybooks in 1842:

3

The Husband's Complaint

I hate the name of German wool in all its colors bright,

Of chairs and stools in fancy work, I hate the very sight

The shawls and slippers, that I’ve seen, the ottomans & bags,

Sooner than wear a stitch on me I’d walk the streets in rags.

I’ve heard of wives too musical, too talkative, and quiet,

Of scolding or of gaming wives, and those too fond of riot:

But yet of all the errors known, which to the woman fall,

Forever doing fancy work, I think exceeds them all...

The speaker's wife answers with her own poem, "The Exculpation (In answer to the husband’s Complaint in the matter of His Wife’s Worsted work":

Well to be sure-I never did-why, what a fuss you make

I’ll just explain myself, my dear, a little, for your sake

You seem to think this worsted work is all the ladies do.

A very great mistake of yours-so I’ll enlighten you.

I need’nt count, for luckily I’m filling in just now

So listen, dear, and drive away those furrows from your brow

When you are in your study, dear, as still as any mouse,

You cannot think the lots of things I do about the house...

Authors of needlework handbooks were well aware of such attitudes. They highlighted how practicing Berlin work emulated the upper classes' needlework pursuits. Despite these efforts, many of these aesthetic criticisms evolved into a more cohesive revolt (

the aesthetic movement/design reform movement) against a perceived industrialized samenesss and aesthetic messiness. Elite design movements aside, many criticisms were based on long-held misunderstandings about Berlin work, such as the idea that it was made using synthetic dyes (not true), that it did not reflect creativity (similar arguments could be made about eighteenth-century needlework), and that it was a waste of time.

I do not have time to into great depth here about each of these issues (hopefully they will be part of a future publication), but I can tell you that Ann Warder and her use of Berlin work shows that it was not a waste of time or a material production unworthy of close analysis (either historically or today).

Eighteenth-century needlework, which tends to be more highly valued that nineteenth-century Berlin work was often made using some of the same methods used by Berlin workers. Unfortunately, it seems that, thanks to the long-standing dislike for the needlework, few have given it serious scholarly attention. Berlin work does not command anything near what eighteenth-century needlework commands in the market place. On a recent trip to an antiques show, while I analyzed a late Berlin work sampler marked 1875, the merchant noted, "clearly she didn't have a lot of skill." And I didn't have $180 to spend on this unskilled piece of needlework, although an eighteenth century example of needlework the same size would have commanded several hundred dollars at the same venue.

Warder's story shows that, like several historians, curators, and other scholars of women's history and needlework have noted, in the eighteenth through the nineteenth century, needlework served as a way to develop and maintain familial and friendly relations.

4 In addition, when it was taught in a school setting, needlework and other "ornamental" arts were seen as complements to the standard "arts and sciences" education.

5 Several Berlin work collections associated with the women's academies and seminaries are extant. Whether Warder attended a school is unclear, but the patterns themselves and Warder's letters and account book show that Ann Warder, like her predecessors, lent her patterns to friends an family and that she bestowed hand-wrought needlework gifts throughout her lifetime. Warder was ill for most of her life, ultimately dying of an "ulceration of the stomach" in 1866.

6 For Warder, making and exchanging needlework provided her life with cohesion and meaning. The album pictured below is a good example of an English counterpart.

Sarah Bland, a "gentlewoman," made this album in 1866 in England. According to the V&A, "the gift of designs demonstrates connections between relatives of merchant and banking families and is of historical significance in bonding between such families." The album contains Berlin work pattern published by well-known German pattern producers such as A. Todt. Given by Mrs D. McGregor, Victoria & Albert Museum, London, E.372:162-1967.

Sarah Bland, a "gentlewoman," made this album in 1866 in England. According to the V&A, "the gift of designs demonstrates connections between relatives of merchant and banking families and is of historical significance in bonding between such families." The album contains Berlin work pattern published by well-known German pattern producers such as A. Todt. Given by Mrs D. McGregor, Victoria & Albert Museum, London, E.372:162-1967.

How does Berlin work--and Warder's story in particular--inform the way we think about needlework, craft, kitsch, fashion, and women's history? Considering the

Elle fashion spread and the history of Berlin work's discourse of criticism, the seminar attendees had some fantastic ideas about what has changed (and what hasn't changed) regarding needlework and craft. Despite the fact that many still consider Berlin work in the same negative light as "kitsch," it continues to be fashionable. The

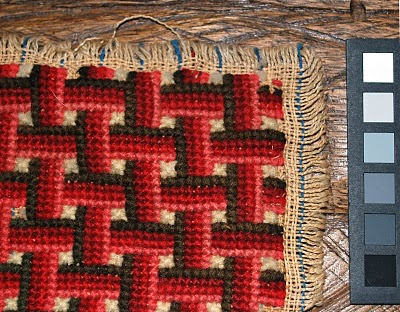

Elle spread suggests that its audience deems "craft" fashionable to wear and also, if you have the skill and the time, fashionable to make. Second, another seminarian pointed out continuities in needlework as a group or communal activity. Similar to the way that eighteenth- and nineteenth-century needlework brought women together, so, too, does needlework today. I bet that you or someone you know participates or has participated in a knitting or other needlework group of some kind. If not, needlework's pervasiveness is inescapable one you start looking for it. My boyfriend noted that most of the tag sales we've patronized over the past few months have included hordes of needlework supplies. Here is another example of mid nineteenth-century Berlin work I picked-up at a tag sale for a few dollars.

Berlin work and Berlin work patterns can be found at museums throughout the United States, Berlin work is sold at auction and in retail settings, and Berlin work is collected. This pervasive remnant of the past continues to be important today, whether it is in the world of fashion, the world of "crafts," or the museum world and antiques market. Its pervasiveness alone suggests its historic importance and its continued importance to those have executed it. Berlin work is a poster child for the importance of studying material culture for the sake of understanding it rather that the sake of its beauty. There is no need to be a snob about this, folks--Berlin work is history too. It also looks great on tabletops and walls when used for decorative purposes.

After the discussion with the University of Delaware "Fashion and Fiber" seminar, I am looking forward to exploring Berlin work's relation to "craft" and "kitsch" in more depth. My next presentation will be at the University of Alberta Material Culture Institute's

"Material Culture, Craft & Community: Negotiating Objects Across Time & Place" conference in May. Click

here to view the program.

In the meantime, please let me know if you have more questions about Berlin work, as I have only scratched the surface here. Also, if you have any images of Berlin work you would like to share, please send them my way! nbelolan at gmail dot com

UPDATE

4 January 2011

Here is an example of a lithographed pattern published in a popular nineteenth-century women's magazine. Patterns such as these were typically included at the beginning of the issue. Some (but not all) were accompanied by a usage note at the rear of the issue. As the 1850s and 60s progressed, more and more patterns (such as this one) featured broader color palettes. Editors boasted about these patterns, noting that readers would spend more on a pattern from a fancy store than on an entire issue of the magazine.

7 Needleworkers could have used this pattern in a number of capacities. Needleworkers may have stitched the design onto canvas and framed it. Alternatively, they may have worked the pattern and used it as upholstery or as a piece of a quilt.

I purchased this pattern at an antique mall in northern Michigan last week for $5. I have seen earlier hand-colored examples of about the same dimensions in somewhat better condition for about $25 to $30. I think $5 was a good price for this pattern, although I am concerned about the Scotch tape that is holding the pattern together where it was folded.

Further Reading

Click here to reference my thesis bibliography

Further Reading

Click here to reference my thesis bibliography.

Notes

1. “She’s Crafty: The Season’s Homespun Needlepoints and Crochets

Offer Equal Parts Kitsch and Comfort,” Elle Fashion Trends, Elle, November

2008, 154.

2. The Warder Berlin Work collection is at the Winterthur Museum, in Winterthur, DE, 2004.0071.001-.148.

3. “The Husband’s Complaint,” Copied by Ann Warder, 5 August 1842, and “The Exculpation (In answer to the husband’s Complaint in the matter of His Wife’s Worsted work,” Copied by Ann Warder, 5 August 1842, in Poetry Notebook, ca. 1841-1844, 12-14, Box 105, J-CFP.

4. Catherine E. Kelly, In the New England Fashion: Reshaping Women’s Lives in the Nineteenth Century (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1999), 55; Amanda Vickery, Behind Closed Doors: At Home in Georgian England (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 245-246.

5. Mary Kelley,

Learning to Stand and Speak: Women, Education, and Public Life in America's Republic (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 76-81.

6. Ann Warder, Death Certificate, Vol. 1, 1866, no. 105, Philadelphia City Archives, Philadelphia, PA.

7. Warder Collection, 2004.71.122, “Pattern for Chair Seat,” Peterson’s Magazine, January 1863, 85 and Warder Collection, 2004.71.108, and “Berlin Work Pattern./For Sofa Pillow, Footstool, Bag, Ottoman, or Fender-stool,” Peterson’s Magazine, December 1860, 484.